At this time of year, when we celebrate Pentecost, we think about the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of God. And we know that we must think about the Holy Spirit if we are Christians and if we are those who believe in Jesus as the Messiah, the Son of God, the Savior and Redeemer of the world, and everything that we say about Jesus Christ, we realize that we can’t say anything about him without saying something about the Holy Spirit and about God himself, God the Father himself. We simply cannot think of Christ, have a relationship with Christ or read about Christ in the Scripture, teach about Christ, without teaching about God the Father and about the Holy Spirit, what came to be called very early in Christian history the Holy Trinity.

That word, “trinity” is not in the New Testament, but certainly the witness to God the Father, to the Son of God, Jesus Christ, and to the Holy Spirit is in the New Testament. And, if we take the Bible as a whole, certainly you cannot at all speak about the God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, the prophets, the God of Israel, the God of the Scripture without speaking about the Word of God that Christians confess is incarnate as the man Jesus and is, in fact, God’s very own Son. Jesus is God’s Son and Word and Image, Icon. And the Spirit: you can’t read the Bible without also always hearing about the Spirit of God, the breath of God.

If we put it very, very simply, we would say, first of all, about Jesus: Jesus being God’s son immediately makes us think about God the Father and what are the qualities and characteristics of God in his activity. When we think of Jesus Christ as the Messiah, the Savior, when we read about him in the Scripture, we know that he was conceived of the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit was upon him as he grew in stature as a man on earth. He’s baptized in the Jordan River, and the voice of the Father says, “This is my Son, my beloved,” and the Spirit in the form of a dove descends and remains and rests upon him. Then it says the Spirit drives Jesus into the wilderness.

Then we know that Jesus began, in Luke’s Gospel, his public ministry by reading from Isaiah where it says, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, to proclaim the glad tidings and freedom to those in captivity and the good news to the poor” and so on. And then, when Jesus begins preaching and teaching, the claim is: it’s all being done by the Holy Spirit, and it is the Holy Spirit by which Jesus says and does everything he says and does, to the glory of God, his Father, and to reveal God, his Father, and to do the work of God, his Father, to speak and to be the Word of God the Father in human flesh, and to accomplish the Father’s will. And Jesus even refers to “the one God and Father and the Holy Spirit” in St. John’s Gospel as the two who bear witness to who he is as God’s Son and as the Messiah and as the Lord.

But just generally speaking, when we think of Jesus Christ, we certainly cannot think of Christ without the Holy Spirit. Then, of course, we know that Jesus promised to give the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of God, the Spirit of truth, to his disciples, and that as a matter of fact, he did. He says that when he is glorified, when he is crucified, raised, and glorified, that the Holy Spirit will come upon his disciples. He will send the Holy Spirit that is from God the Father, or God will send the Holy Spirit through the world, through him.

And here, let’s just read a couple of texts from the Holy Scripture. St. John, the theological Gospel, that simply say this in so many words. First of all, in John 14, Jesus says:

If you love me, you will keep my commandments. I will pray the Father, and He will give you another Counselor, another Parakletos, to be with you forever, even the Spirit of truth, whom the world cannot receive because it neither sees him nor knows him. You know him, for he dwells with you and will be in you.

So it’s this: the Father will give you the Spirit. God the Father will give you the Spirit. In that same 14th chapter, 25th verse, it says:

These things I have spoken to you while I am still with you, but the Counselor, the Comforter, the Parakletos, the Paraclete, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, He will teach you all things, and he will bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you.

So Jesus says the Father will send the Holy Spirit in His name, the name of Christ, to bring to remembrance all that Jesus himself has said, and even to give the understanding [of] what Jesus himself has done. In the 15th chapter of St. John, you have the same thing repeated. I’ll read it: “But when the Counselor comes”—again, that word “Counselor, Parakletos, Advocate, Comforter”; it’s translated various ways—“whom I shall send to you from the Father…”

And here Jesus says, “I will send to you from the Father.” Before, he says, “The Father will give you, the Father will send to you through me and in my name.” Here he says, “I will send to you the Spirit of Truth from the Father.” The Spirit of truth that comes from the Father, I will send to you, and then he says, “Even the Spirit of truth Who proceeds from the Father.” You have that sentence there: “Who proceeds from the Father.” “And He,” meaning the Holy Spirit, “will testify, will bear witness to me, and you also are my witnesses, because you have been with me from the beginning.”

In the 16th chapter, you have this very same teaching again, repeated. Jesus says, “I tell you the truth: it is to your advantage that I go away, for if I do not go away, the Counselor”—again, the Paraclete, the Comforter, the Advocate—“will not come to you. But if I go, I will send him to you.” So here again, he says, “I will send him to you.” “When he comes, he will convince the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgment.” And then he goes on and says:

I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now, but when the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth, for he will not speak on his own authority, but whatever he hears, he will speak, and he will deliver to you the things that are to come. He (the Holy Spirit) will glorify me, for he will take what is mine and declare it to you. All that the Father has is mine, therefore I said he will take what is mine and he will declare it to you.

Now, of course, in the New Testament, the Spirit is called the Spirit of God. He’s called the Holy Spirit. He’s called the Spirit of the Lord: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me.” He is called the Spirit of Christ. So you have this witness to the Spirit in the New Testament. Now if you take the Old Testament, right from the very beginning in creation, you have God always speaking and acting by his Word and by his Spirit. He creates the world through his Word, according to Genesis, but on the first pages of Genesis, it says, “The Spirit of God, the breath of God, the wind of God,” because “breath” and “wind” and “spirit” are all the same word in Hebrew: the ruach of God “is brooding over the abyss.” And in the Old Testament Scriptures, the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of God, accomplishes everything that God does, and the agent of God’s accomplishment, even in the Old Testament, is his Word.

The Word of God, in Hebrew, the word “word,” it doesn’t just mean a concept or a spoken word; it means an act; it means a thing. The very same word means “word,” “act,” and “thing.” So God is doing his thing, he is doing his action by his word. Isaiah says, “The word of God will come and accomplish that for which it has been sent.”

Not only is God creating the world by his Word and his Spirit, his breath and his wind, but if you read the entire Old Testament, you will see that every time God speaks, his word, his revelation, his truth, is vivified by his very own Spirit. And wherever the Spirit of God comes, he brings the Word of God. St. John of Damascus, who was a Semitic man, a middle-Eastern man, although he wrote in Greek, he said in the Biblical symbolism, whenever God speaks, his word he breathes, and every time he breathes, he gives a word, he gives a meaning.

The word of God is not dead; it’s alive, it’s living, and it’s active. That’s what the Letter to the Hebrews will say in the New Testament: “The word of God is living and active, sharper than a two-edged sword.” But it’s living and active because it’s a live Spirit, because the Spirit of God is within the Word. And then, the Spirit of God itself is not dumb. It is not Word-less. God is not Word-less. God is not Spirit-less. God is the living God who speaks, who acts, who touches. And this is the vision that we have of God in the Bible.

So the one, true, and living God of the Law and the Prophets is the God who is always acting, as St. Irenaeus said in his writings (a Christian bishop of the third century). He said: the two hands of God: the Scriptures speak of God working with his hands. Well, his two hands: one is his Word and one is his Spirit, and the Spirit and the Word are always together. And we see that in the New Testament when the Word becomes flesh and the Holy Spirit is in Jesus, on Jesus, with Jesus, acting through Jesus, and everything that Jesus does as the incarnate Word of God to reveal God, to show God, to bring God to the world, the God who is his Abba, Father, is done by the activity of the Holy Spirit. And, of course, the people who were against Jesus, they said, “He does these things by the devil,” and he says, “No, they are by the Spirit of God.”

Now, the prophets themselves in the Old Testament, the Creed says about the Holy Spirit, “He spoke through the prophets.” So the prophets announced the word of God. They say, “Thus says the Lord,” but they do it because they’re vivified by the Holy Spirit. Even the Law itself, the Torah of Moses, it is God’s word because it is inspired, it is God-breathed, it’s breathed by the very Spirit of God. So the Scriptures show the Trinitarian character of God. They are the incarnate word of God in words inspired by the Holy Spirit. The prophets do the same thing. They speak the word of God, inspired by the Holy Spirit.

So you have the Word of God and the Spirit of God, and Jesus is the Son and Word and Icon of God, never devoid of the Spirit of God. And that same Spirit is sent upon the Christians by the risen Christ so that they could be christs and sons of God themselves, that we could be sons of God. St. Paul says this: God pours his Spirit into our heart, crying, “Abba, Father!” And the Apostle Paul will say no one can call God “Abba, Father,” no one can call Jesus the Son of God and the Lord, unless he be inspired by the Holy Spirit.

So we receive the Holy Spirit as a gift as Christians. The personal gift of the Holy Spirit is given to us so that we could have all the qualities of God: love and peace and joy and patience and kindness and goodness and gentleness, that we could know the truth, that we could have wisdom, because the Spirit is the Spirit of wisdom; that we could live forever, because he’s the life-creating Spirit; we would know the truth because he’s the Spirit of truth. So the Spirit is there at all times.

What happened in Christian history which is what we want to discuss particularly today is about the origin of the Holy Spirit and the activity of the Holy Spirit and the relationship of the Holy Spirit to the one God and Father and the relationship of the Holy Spirit to the Son of God, Jesus Christ. In the earliest Church, when the Christians were formulating the faith, particularly formulating credal statements to be used at baptisms, so that the people who were being baptized could confess the faith in a brief form, usually called a symbol or symbolon of faith, a credal statement, a creed—“creed” comes from the word “credo, I believe”—what was said about Jesus Christ we know. First of all, what was said about God, we know: “We believe in one God, Father Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth.” And then we confess we also believe:

I believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, God’s only-begotten Son, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not created, of one very same divinity with the Father, who for us men and our salvation came from heaven, was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary and became human.

And then he was crucified, he died, he was buried, he was raised, he is glorified, and he will come again in glory. Now that was said at the Council of Nicaea which then ended its definition, simply, “And we also believe in the Holy Spirit.” That was the year 325; that’s the Council of Nicaea.

In 381, which we now call the Second Ecumenical Council, an addition or the completion of the Creed was made, where a statement was made, a very brief statement, about the Holy Spirit. It said, “And we believe”—and we say when we’re baptized, we say at the Divine Liturgy, “I believe”—“in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and the Giver of life, who proceeds from the Father, who with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified, who spoke by the prophets.” That is what the Creed says. And then, of course, it continues:

And I believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. I acknowledge (or confess) one baptism for the remission of sins. I look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the age to come.

And there you have the Creed. There you have the Symbol of Faith.

Now, about the Holy Spirit, the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, the Creed that was written—the first part in Nicaea, the second part in Constantinople; 325, 381—that’s our statement of faith. And about the Holy Spirit, it said, again: “I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of life.” “Lord and Giver of life” has to mean that he’s divine. “Kyrios” is the divine Name. He’s the Lord. He’s called the Lord in the Holy Scripture; certainly by St. Paul, he’s called the Lord. And the life-giver, the vivifier, the one that makes things alive, as the Christian prayer, the ancient Christian prayer which we still use in the Orthodox Church will say, “O heavenly King, the Comforter, the Spirit of truth, you are everywhere and you fulfill all things,” you do all things, you accomplish all things; you fill all things and you fulfill all things, “you’re the treasury of the good things, the giver of life,” and then we pray that this Spirit would “come and abide in us.”

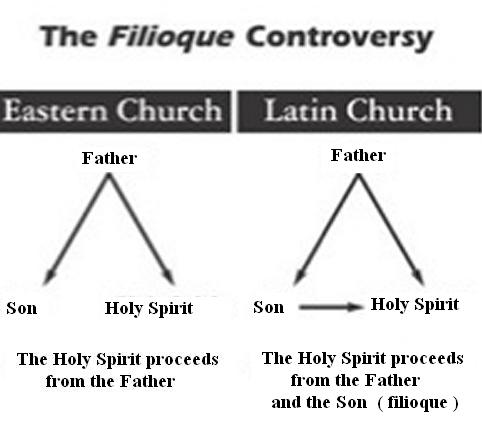

What happened in Christian history, however, which is very, very sad, is that, in the Western Church, a word was added to this Creed that changed the teaching. It changed the teaching. And it had to do with the Holy Spirit. And that word is “filioque.” It’s one word in Latin, and it means “and the Son.” And the term “filio” is the ablative case of “filius,” which means “son,” and so when the Creed said, in Latin, “and in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of life, the Spirit who proceeds from the Father—ex Patre procedit is what it said in Latin originally: ex Patre procedit—they added the term: ex Patre filioque procedit. That the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father filio-que, and from the Son. “Filio” means “the Son,” or “from the Son,” and “-que” on the end of a word means “and”; it just means that you have an “and” there.

So this one word was added to the Creed. Now, the question is: where was it added to the Creed, why was it added to the Creed, and is it proper and fitting that it would be added to the Creed, and, if it is added to the Creed, how is it to be understood and certainly how is it to be understood in relationship to what the Creed originally said? And then, of course, the question also has to be very clearly asked: was it in the original Creed and was it dropped, or was it not in the original Creed and was it added?

Everybody in the whole world today knows and always did know, except, I think, at one certain period in history which we’ll talk about in a second, that it was not in the original Creed. It was added to the Creed. Now, where was it added, why was it added, and is it right to be added? This is what we want to talk about now for the next few minutes, because the addition of that word, filioque, to the Creed caused a real theological division between the Roman Catholic Church and the Protestant churches on the one hand, and the Orthodox Churches in the East, both the Chalcedonian Eastern Orthodox Churches and the Eastern Churches, the Oriental Orthodox, who do not accept the formulation of the Council of Chalcedon.

And some people really believe that, together with the Roman Catholic doctrine about the papacy, the infallibility of the pope, the filioque was, not only the major doctrinal, dogmatic, theological controversy that caused the division between the Churches when there was a real disagreement on how to understand Christ and God and the Holy Spirit and their relationships to each other, it became a real Church-dividing issue. And it’s a Church-dividing issue to this very day, although in recent time, the Western Churches are confessing pretty much that it wasn’t in the Creed, it shouldn’t have been there, it’s better to put it out, and even the Roman Catholic Church, that still has it, and the Protestant churches that still have it and still use it, say it’s okay if the Orthodox [Churches] don’t have it.

But the Orthodox Churches, generally, still say the Western Churches should not have it either because it is wrong. It is theologically and doctrinally wrong to say, and, also, it should not have been put into the Creed in the first place, and also, in the Creed itself, it was a quotation of Holy Scripture. So if you add it, you’re changing the meaning of the Scripture, because the claim is that that sentence in the Creed, where it says, “the Holy Spirit who proceeds from the Father,” that “who proceeds from the Father” is a quotation of St. John’s Gospel. I already read it to you. It’s in the 15th chapter, 26th verse: “But when the Counselor comes, whom I shall send you from the Father, even the Spirit of truth who proceeds from the Father, he will bear witness to me,” Christ says. So it says that you’re adding words not only to the Creed, you’re adding words to the Bible, because the Bible does not say that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son.

How did all this happen and how are we to understand it? Well, it’s a very complicated issue. It’s a very difficult issue. There’s a lot written about it, and I would just mention two books that are very important if you’re really interested in this. There’s a book written by Richard Haugh. It was published in 1975. Richard Haugh was a young Christian scholar at the time, and he wrote the book called Photius and the Carolingians. Why I mention that book is because this whole issue came to a head in the ninth century when St. Photios the Great, the Patriarch of Constantinople, simply said to the Western churches, “You should not have this in your Creed,” that it is wrong to have.

And then the Western Christians, particularly the Carolingian theologians—those were the barbarian theologians, the Franks and the Germans who had converted to Christianity in the Roman Catholic Church, but they were not Latins; they were Franks and Germanic people—they defended very strongly and radically the filioque, and even defended that it belonged in the Creed and even defended that it was in the Creed in the first place.

So a huge, big… There was a turmoil before, there was discussion earlier, but it really broke loose in the ninth century, in the 800s, and then it finally led to a formal division between the churches at the beginning of the 11th century when the Creed, with that word in it, was sung in Rome by the bishop of Rome in the Latin Church, of the Western Church. In other words, it won the day, and it created… It was a great contributing cause to the division between the Latin Church (the Roman Church, the Roman-Frankish Church, Germanic Church) and the Eastern Churches, particularly Greek-speaking, Syriac, and so-on-speaking churches. And it’s a cause of contention down to this present day.

Now, this book, Photius and the Carolingians by Richard Haugh, it really gives a very nice history of this whole issue and how it did come to a head, beginning already in the seventh, eighth, ninth centuries, and then how it led to this division and what the story was about.

There’s another book published by the World Council of Churches. I can’t remember the exact date now, but it was called Spirit of God, Spirit of Christ, and it was a study by high-ranking theologians from virtually all the Christian churches—Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestants—about this issue. And basically, that particular statement, Spirit of God, Spirit of Christ, the papers in that book—it’s published in Geneva; you could find it online, I’m sure; it’s called Spirit of God, Spirit of Christ: World Council of Churches Papers—it really came out and said, “This word should never have been added to the Creed, and it’s better that this word not be there, and for the sake of Christian unity, it would be better if it were simply dropped from the Creed and none of the Christians who used the Creed would use this word any more.

But of course, that did not happen, although some of the Protestant churches did drop the word, and the Eastern rite churches in communion with Rome no longer use that word, but, nevertheless, the Latin, Roman Catholic Church, of the Latin rite, and virtually all of the Protestant churches that use credal statements would still use the Creed with the filioque in it if they use the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed. But there was also an earlier creed, sadly, misleadingly called the Athanasian Creed, that did have a sentence that said that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, and that was very early already in the fourth, fifth century.

So what’s the story? Let me try to make this as simple and as clear as I can for you. And in some sense, it really is not very complicated. If you read it carefully, even in the details, you can see that there’s a pretty clear pattern that’s really rather hard to dispute in what actually happened. This is it in a nutshell: The greatest theologian in the Western Church was St. Augustine of Hippo. And Augustine wrote a book, De Trinitate, and it was a very, very bad book, theologically.

In fact, St. Augustine, he wrote this, he said, “This is my opinion. Maybe I’m mistaken; maybe it should be corrected.” And the joke, when I was a theological student and a teacher was, “and the Christians of the East have been correcting it ever since,” because, simply, it is a very poor formulation about the doctrine of the Trinity. There’s many good biblical things in there, many good psychological, spiritual things, but metaphysically, theologically, it isn’t very good. And, without getting into why or how, but in any case, for the sake of our little talk here, St. Augustine clearly taught that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Fatherand the Son, that the Father and the Son together are both God, and the Spirit is the Spirit of God, it’s the Spirit of Christ, therefore the origin of the Holy Spirit is in the Father and the Son.

But already in St. Augustine, there was a mixing together of what would be called, traditionally in [the] Eastern Church, theologia and oikonomia. In other words, what do we say about the Godhead from all eternity and the relations of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and then, what is said about Christ in the oikonomia on earth, of salvation, when he sends the Holy Spirit from the Father to his disciples? Because what will happen is that when Jesus will say, “I will send you the Holy Spirit,” the simplistic answer was, “Oh, then the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Son, too.” But actually, even in the Scripture it says, “I will send you the Holy Spirit, who proceeds from the Father.”

And then, the Scripture says a lot of times that the Spirit is the Spirit of Christ, the Spirit of the Son. And the Son really is divine with the same divinity as God the Father. That’s the teaching of Nicaea. Therefore, if the Spirit is the Spirit of God and proceeds from God the Father, then the Spirit should proceed from God the Son as well. And then it even developed that, since the Son is “Light from Light and true God of true God,” and he is really divine, so you could say the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, as if from one principle, that the Father and the Son form like one originating principle of the Spirit of God who is sometimes even described as the love between the Father and the Son: the Father loves the Son, and that love is the Spirit; the [Son] loves the Father, that love is the Spirit, and the Spirit is a kind of a divine force or Person that unites the Father and the Son.

So there’s a lot of Biblical exegesis and metaphysics and Platonism and all kinds of things involved, but in any case, what we want to see is that St. Augustine did teach that you could say and teach and be right that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. However, when Augustine was in Church and the Creed was being read, it did not have the filioque in it. It simply said, “I believe in the Holy Spirit who proceeds from the Father.” And then, as St. Augustine said, “Yes, but you can further explain if he proceeds from the Father, he must proceed from the Son, too, because the Son is God from God and Light from Light and he’s really divine with the same divinity.” But then, the whole thing started getting very mixed up and confused.

Well, to add to the confusion, the barbarian invaders in the West, particularly the Goths and the Visigoths, had been converted to Christianity as Arians, as Arian Christians, not as Orthodox Christians. And the Arian Christians denied the divinity of the Son and Word of God. They denied the divinity of Christ. They said, “Yes, God has a Spirit, and a Word, but the Word and the Spirit are not divine in exactly the same way as God the Father. They are somehow lesser gods, if gods at all.”

And then the extreme Arians even said that the Word of God and the Spirit of God are creatures: God made his Word; God created his Spirit. He kind of willed them into being, that they are not part of his very being, and therefore they are not God. So the Arians were Unitarians, and only God the Father was really God. The Son and the Spirit were not really divine and were not really God.

Now, when the Orthodox Catholic Christians of the West, the Romans, were fighting against these Arianizing Goth Christians, they wanted to really affirm the divinity of Christ. They wanted to be really Nicaean, because [the] Council of Nicaea said that Jesus Christ is God. He is God from God. He’s the Son of God, begotten of the Father before all ages. And so, even though they had the Creed that said about the Holy Spirit “who proceeds from the Father,” they interpolated the Creed, they somehow added to it, they wanted to clarify it especially to insist on the divinity of the Son of God and Christ by putting the word “filioque” into the credal statement itself.

And so there is a council in Spain, 589, where that council in the West actually, in some sense you might almost say “officially,” placed the filioque into the Creed, and the Creed there was taught in the Western Church, and they thought that it came from a Creed that was from St. Athanasius. It was called the Athanasian Creed, or called Quicumque in Latin, where it says, literally, “The Holy Spirit is from the Father and the Son, not made, not created, nor begotten, but proceeding.” And it says, “He who wishes to be saved should think thus of the Trinity.” And again saying that the Spirit is from the Father and the Son in its origin.

Everyone would have said the Spirit comes from the Father and the Son in the mission to the world, its origin is in God the Father, it’s the Spirit of God; but the Spirit proceeds from the Father, it rests in the Son of God. The Son of God comes on earth as Jesus, and he gives the Holy Spirit to his disciples. He breathes on them and gives them the Spirit that is in fact the Spirit of God that he himself has received eternally from God the Father.

What happened was that this council in Toledo, where it was going against the Visigothic kings and so on, wanted really to insist that the Spirit came from the Father and the Son, to insist on the divinity of the Son. Now, it admitted in the very canons of the council and according to the form of the Eastern Churches that has to be chanted in the church, the 150 Fathers in Constantinople, the Second [Ecumenical] Council, said that you should say, “the Holy Spirit who proceeds from the Father,” so let’s continue to say that, but we have to believe that that means the Spirit comes from the Son as well. And then the word actually got put into the Creed in order to make this affirmation.

So there you have a problem. You have Fathers teaching that the Holy Spirit comes from the Father and the Son, but not saying it in the Creed because the original Creed did not have it, but still teaching it, still somehow believing it. And then there were some, including many popes, who said, “Yes, it’s right. St. Augustine is our holy father,” and all the holy theologians who followed Augustine said, “Yes, the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son,” but they still were against putting it in the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed in church. They said you can teach it, it’s a theological doctrine, it’s perfectly fine, but let’s keep the Creed the way it was originally written.

Those who had been trained in the theology of Augustine in the West—and that meant just about every one of the Western Fathers: Ambrose and Gregory the Great, even Pope Martin in the seventh century, the great friend of St. Maximus, who was killed and arrested by those heretics of the seventh century—they all were pretty much teaching the filioque, but denying that it should be put in the Creed. And there was even the pope named Hadrian, Pope Hadrian, in the eighth century, who said that the teaching of the filioque is in the perfect accord with the Roman see, and he even stressed that the doctrine can be taught in Latin and Greek Fathers, and he quoted selections of Athanasius, Gregory of Nyssa, Hilary, Basil, Ambrose, Gregory Nazianzen, Cyril of Alexandria, Pope Leo the Great, Pope Gregory the Great, Sophronius of Jerusalem, St. Augustine of course.

But St. Augustine is the main guy here, the main teacher. But these others, they more or less said these things in passing, and the Western Fathers had received this theological tradition, so you had this anomaly. They were teaching that the Holy Spirit is proceeding from the Father and the Son, or comes from the Father and the Son, is the Spirit of the Father and the Son. They weren’t too technical about it; they weren’t insisting too much about it. And, at the same time, in church, at the Liturgy, they were not saying “filioque.” It was not in the Creed at all. It simply was not there.

What happened at the time of the Carolingians was that the Carolingian theologians, the Germanic and Frankish theologians—and all of this began… they’re called “Carolingian” because of Charlemagne, Charles the Great, and so on—they needed to have the filioque in the Creed, not only because they really believed that it was true, but because they wanted to be against the Easterners whom they knew did not have it, and in their ignorance they accused the Easterners of having dropped it, because they were all convinced, because it was so traditionally taught, and since Toledo, it was even in some credal statements, that it simply was a classical teaching of Christianity. They just didn’t know.

In the year 800, Charlemagne, Charles the Great, who wanted to reestablish the Empire in the West, was crowned as the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, in Rome, by the pope of Rome, and it was the beginning of what came to be called in history the Holy Roman Empire, which the English historian, Gibbon, says was “neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.” It was not very holy. It certainly was not Roman; it was Frankish, it was Germanic, it was barbarian, using the language of the time. It was not traditionally Latin. And it was not even an empire.

Now, this Charlemagne, he had to affirm himself as an emperor in the West. He had his seat in Aachen. He had his theologians like Alcuin. They were all Augustine-trained, -minded theologians. So he had to accuse the East of heresy. He couldn’t say that the Eastern Church wasn’t there. He couldn’t say that there wasn’t an emperor in Constantinople. So he did two things: he accused the Eastern Church of worshiping idols because of the icons and he accused the Eastern Churches of distorting the doctrine of the Trinity by dropping the word “filioque” from the Creed, because the filioque was sung in all the Germanic, Frankish churches at that time, but it was not sung in Rome.

Interestingly enough and very important is that the popes of Rome knew very, very well that the Frankish theologians and emperors were wrong. And so you had popes like Pope Leo III in the year 810—I already mentioned Hadrian in 772-795; later there was Pope John VIII, [872-882], at the time of St. Photius—who were… this is how they were dealing with it: they said you can teach it theologically, you can explain the Trinity as the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father and the Son, and they based it simply on the texts that Jesus breathed on the people; gave the Spirit; the Spirit is called the Spirit of Christ; the Son was God, the Father was God, so the Spirit is the Spirit of both of them.

So they didn’t see anything particularly wrong with teaching that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, but they were adamantly opposed to inserting it illicitly into the Creed. They said—the Council of Ephesus, the Council of Chalcedon both said that you cannot amend or change or alternate either the meaning or the words of the Creed. Now, they would argue, “We’re not really changing the meaning; we’re just explaining it better and fuller and interpolating it more deeply, but as far as the words go, we have no right to change it.”

It’s interesting that both Pope Leo III and John VIII, they made shields, they made plaques of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed written without the filioque in it, in both Latin and Greek, and had them publicly displayed on the doors of St. Peter in Rome and publicly saying, “Teach this, but don’t sing it and don’t say it when you say the Creed in the church, because we must keep the Creed as originally formulated.” So they actually saw it as a kind of a theological distinction, but not something to be really pressed. And they certainly were for not changing the Creed.

But to make the story very short and very quick right now, is that that didn’t persist. It didn’t hold, so to speak. That position did not hold. Little by little, this use of the filioque spread. It became part of the polemics. The German missionaries like, for example, dealing in Bulgaria, they wanted to say, “We have the true Creed with the filioque; the Greeks have a false Creed without the filioque. The Greeks don’t have the full doctrine of the Church. We are not changing the meaning of Nicaea. We are increasing it, we are explaining it, we are making it clearer.” And the Easterners were saying, “No, you’re not. You’re distorting it. It’s terrible. You shouldn’t do it.”

So what happened was a real clash. The leader of the Eastern Church, theologically, came to be a very famous patriarch of Constantinople in the ninth century, the 800s, named Photius the Great. And Photius really took on this issue theologically, and that’s why Professor Haugh’s book was called Photius and the Carolingians, because he faced it directly, and he simply said, “Not only is it wrong to have it added to the Creed,” which all the popes would agree with, and St. Photius would even argue against this theology; he said, “Your own popes of Rome do not have it. Leo III, John VIII, they made shields, plaques, without it. They’re telling you you’re not supposed to add it.”

And he’s very much insisting that the Roman popes were very, very to be praised and glorified for not adding this word to the Creed, even though they permitted it and even sometimes supported it as being taught, following the Trinitarian philosophy of St. Augustine and his disciples through history, whose theology, according to Photius the Great and subsequent Eastern teachers like Gregory of Cyprus and so on, that it simply was wrong. It really did distort the doctrine.

The arguments of the Eastern Church, particularly of Photius the Great, without getting into the big metaphysical teachings about how a Spirit can come from two different sources or from two sources as one and so on, put it in the most simplistic form, the teaching was simply this: the Bible says the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father, period. It’s a quotation; you can’t change that. And anyway, it’s not right that it proceeds from the Father and the Son. It is right to say that the Spirit is the Spirit of Christ, because everything that the Father is and has is given to his Son, but that does not mean that the metaphysical, ontological origin of the Spirit of God is the Son of God. It’s not the Son of God; it’s the Father alone. And Photius would use that expression: “from the Father alone,” not from the Father and the Son together, even not together as if from one.

If the Spirit came from the Father and the Son together as if from one, what is that one? Is it a fourth Person of the Holy Trinity? Do you have the Father alone, the Son alone, and then the Father and the Son together producing the Spirit as some kind of new reality? It just is a distorted doctrine. It’s just unnecessary, un-Biblical, and doesn’t make sense whatsoever.

Photius also would say you could certainly say that the Spirit is the Spirit of the Son, because he is: proceeds from the Father and rests in the Son. That will become the great formula: proceeds from the Father, rests in the Son, and through the Son and by the Son is given unto us in the oikonomia of salvation when Christ is on earth.

So Jesus can say, “I will send you the Spirit,” because the Spirit is his Spirit, but it’s the Spirit of God that is in Jesus because he’s the Son of God. The Word of God and the Spirit of God are both of God. The Cappadocian Fathers—Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, Gregory of Nyssa—will simply say the archē of divinity, the principium divinitatis in Latin, the archē theotitos, is the Father alone. The Father is the cause. The Father is the source of the Spirit and of the Son: the Son, by way of generation or procession, being born, he’s a Son; and the Holy Spirit, breathed forth or proceeding from God the Father.

St. John of Damascus will say, and had said before Photius, a century before, that the begetting of the Son of God, in all eternity, and the procession of the Holy Spirit, they are simultaneous acts, although there’s no time in God. He called it “symparomartoun.” He had a special Greek word, saying, when the Father begets the Son, he breathes forth the Spirit, and in breathing forth the Spirit, the Son is generated, and the Son is generated by the power of the Spirit, and the Spirit is on the Son within the Trinity. And we know all of this because we contemplate how the Spirit relates to Jesus Christ in the Incarnation.

As far as God’s mission in the world of salvation is concerned, it is certainly true that the Spirit of God is in and on Jesus Christ, the Son, and the Son of God gives the Holy Spirit to his disciples. He sends the Holy Spirit to his disciples. But the Father gives the Spirit through him. The origin of the Spirit is not the Son, but the Son is the agent by which the Spirit is given to human beings. That is certainly correct, and that is how Photius the Great understood the Christian Fathers of the East and of the West when they appear to be, so to speak, “soft” on filioque. When they said, “Oh, yeah, you can understand it that way. It’s okay to understand it that way, because basically what it means is that, in the activity of God toward the world, that this Holy Spirit is given to us by Christ. Christ gives us the Holy Spirit. It’s the Spirit of God that’s in and on him, and then he gives it to us.” So this is how Photius and those who formulate it said that it was right.

Photius admits that there are passages… Of course, he did not like St. Augustine’s teaching at all, but there are passages in other holy Fathers, like Ambrose of Milan or Cyril of Alexandria, even Maximus the Confessor, because Maximus the Confessor knew that St. Mark, the one who suffered and died with him for the Christological heresy of that time was kind of teaching a filioque teaching, practically. But St. Maximus said, “All he is saying is that the Spirit is given to us in and through and by Jesus Christ, but the Spirit is still the Spirit of God alone.”

When you can quote those Fathers of the East and the West who may have taught it, what Photius says is that they were not strict enough. They were not disciplined enough. They weren’t dealing with the same issue as was now being dealt with, namely, the relationship of the Son and the Spirit to the Father from all eternity in the Godhead. They were mixing together what the tradition would call theologia—that’s the eternal relationships of the Persons—and the oikonomia—the activity of God in history for our salvation. And that’s what led them astray.

There is a marvelous sentence of St. Photius which I’d like to read to you now, where he says why some of the holy Fathers might have been mistaken on this point, and they were mistaken because they didn’t realize what was really at stake, which only became clear later. This is what he said:

If certain Fathers had spoken in opposition when they debated the question [which] was brought before them and had fought it contentiously or had maintained their opinion and had persevered in this false teaching…

In other words, if they were somehow teaching a doctrine that the Holy Spirit somehow proceeds from the Father and the Son.

...and when convicted of it, had held to their doctrine until death, then they would necessarily be rejected together with the error of their mind.

So he said if these Fathers knew what was at stake and had been questioned and would have held to it, then they would be mistaken and they would have to be rejected.

However, if they spoke badly or for some reason not known to us, deviated from the right path but were not strictly questioned, no question was put to them nor did anyone challenge them in order to learn and clarify the truth, we admit them to the list of holy Fathers as if they had not said it, because of their righteousness of life, their distinguished virtue, and their faith, and their being faultless in other respects.

Like for example, Pope St. Martin. He was absolutely faultless in his teaching about Jesus Christ being perfect God, perfect man, two natures, two energies, two wills, and got imprisoned and killed for holding that. But nobody questioned the issue of the Holy Spirit and so on to him, and it was never really raised. In fact, it was never even raised to St. Augustine himself. It just simply never happened. So St. Augustine may have been faultless in many other respects, but not in this one. St. Photius continues:

We do not, however, follow their teaching in which they stray from the path of truth.

So St. Photius says some of the holy Fathers may have strayed from the path of truth.

We, though, who know that some of our holy Fathers and teachers strayed from the faith of true dogma, do not take as doctrine those areas in which they have strayed, but we embrace the holy men. So also, in the case of any who are charged with teaching that the Spirit proceeds from the Son. We do not admit what is opposed to the word of the Lord, but we do not cast them from the ranks of the holy Fathers.

So he says the issue wasn’t clear, it wasn’t debated, it was very murky, it was very mixed. Theology was being mixed with soteriology, the teaching of God in relation to salvation. There were Scriptural texts that had to be clarified, he said, so that can happen. But once it is clear what is being said and what is happening, then you have to be clear. And he said, theologically it is very clear that the Holy Spirit proceeds originally and in his origin from the Father alone.

The Son is born of the Father alone, but the Son is born from the Father by the cooperation of the Holy Spirit, and the breathing-forth of the Spirit is done by the cooperation of the Son, and even somehow the agency of the Son, and the Spirit proceeds from the Father, rests in the Son, and through the Son is given to us in this world. And the Holy Spirit is the one who enacts and accomplishes all the activities of God, the agent of every activity being the Son of God, from creation to salvation to redemption to deification. And the Spirit is taking what belongs to Christ and it’s given to us, and Christ has everything he has from God his Father. So that’s the clear teaching.

So the conviction would be: filioque is wrong. It should not have been added to the Creed in the first place, but it may have been explained acceptably as far as the mission of the Spirit in the world is concerned, but it cannot be justified theologically, and it certainly cannot be justified Scripturally by proper exegesis of the Bible. You just cannot do it.

Well, the West persisted in it. And to make the story really short, by the beginning of the 11th century, the first decade of the 11th century, around 1004, it actually was accepted in Rome, and it was sung at the Mass in Rome. Then Rome, who was in a high point at this point, and putting out its power, claimed, “You must have the filioque in the Creed, or you are wrong.” And so, at the Council of Lyons in the 1270s, in the Council of Florence in the 1430s, the Latin Church insisted you must have filioque in the Creed, and you must explain it in the way the Latin scholastic theology explains it, following St. Augustine, or you are heretical.” And the Eastern Churches in response said, “If you explain it that way, you’re the ones who are heretical. You are teaching the false doctrine.” And so this has remained up to the present time.

In the last century, there were a lot of meetings, discussions about this, and it seems that the theological community, even in the Roman Catholic Church, would say that filioque does not belong in the Creed, and the explanation of the procession of the Spirit, metaphysically, is from the Father alone, but you can say that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son relative to us and to our salvation. So filioque would actually be interpreted as “per filium, through the Son” or “by the Son” or “by agency of the Son,” but that the Son would in no way, either alone or together with the Father, in any sense be the origin of the Holy Spirit. The Spirit is the Spirit of God the Father alone, but that very Spirit is the Spirit of the Son of God from all eternity, because everything that God the Father is, he gives to his Son, and he even gives the Spirit to the Son of God divinely in all eternity, and then, when Christ is on earth, the Spirit of God descends and remains on him, and he does all of his activity as a man by the Holy Spirit as well.

This is what that filioque is all about. It was about an addition of the word to the Creed, which should never have been done, which may be explained, when it’s explained kind of sloppily and mixing everything all together; it might be justified, but when you become very strictly articulating theological truth, then it is not justified at all. The Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father alone, although it’s sent into the world, given to the world, through the agency of Christ, and the Spirit is the Spirit of Christ.

The Carolingian theologians, by the way, they made a big deal that Scripture says the Spirit is the Spirit of Christ. They said, “If the Spirit is the Spirit of Christ, then he proceeds from Christ.” The Greek theologians, the Eastern theologians, said, “That’s nonsense. The Spirit is the Spirit of Christ, but the Spirit is the Spirit of Christ because first it’s the Spirit of God the Father from whom the Holy Spirit proceeds and from all eternity dwells and rests in the Son of God from all eternity in the mystical unity of the Holy Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

So if you’re interested in this, I would simply suggest to you the book Photius and the Carolingians by Richard Haugh, and I would suggest to you to get that World Council of Churches paper, published, I believe, in the 1980s, called Spirit of God, Spirit of Christ, where scholars of all the churches really show what is at stake and basically justify the Eastern Orthodox ancient position, even the position of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, that the filioque, at best, can be used and explained in a very particular way concerning the activity of the Spirit coming through Christ for the sake of our salvation, but in absolutely no way can it be accepted in the Trinitarian theology of God from all eternity.

It would be Orthodox dogma that the Holy Spirit is the Spirit of God, proceeding from the Father, resting in the Son, as the Spirit of the Son, and through the Son is given to us.