|

|

Orthodox Outlet for Dogmatic Enquiries | The Fathers |

|

Why did Elders choose the desert? From the book : "In the Heart of the Desert: The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers"by Protodeacon John Chryssavgis |

|

Chapter 4

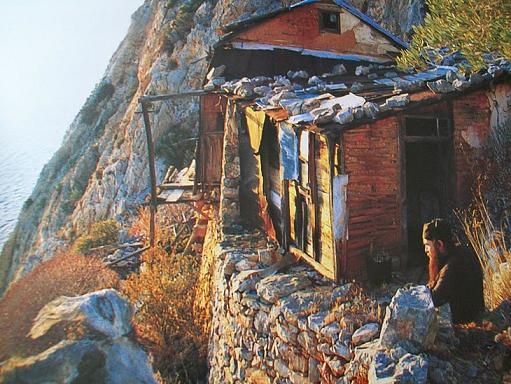

Why did these elders choose the desert in the first place? What was the

significance of the desert? What is the power of its suggestion?

"Desert" (eremos,

Ýñçìïò)

literally means "abandonment"; it is the term from which we derive the

word "hermit". The areas of desertedness were where the demons bred. In the Book of Leviticus, the desert

is the place that is accursed (Lev.16.21). There is no water in the

desert, and in the mind of the Jews that was the ultimate curse. No

water also meant no life. The desert signified death: nothing grows in

the desert. Your very existence is, therefore, threatened. In the desert

you will find no one and no thing. In the desert, you can only face up

to yourself and to every aspect of your self, to your temptations, and

to your reality. You confront your own heart, and your heart's deepest

desires, without any scapegoat, without any hiding place. It is in the

desert that Jacob battled; and it is in the desert that you do battle

with the unruly forces of your nature within and without. The desert was

filled with the presence of the demonic.

Abba Elias said: "An old man was living in

a temple of the desert, and the demons came

to him, saying: 'Leave this place; it belongs to us.'"1

Yet, the desert was also endowed with sacred significance for Jews and

Christians alike. The Israelites had wandered in the desert for forty

years. It was there that Moses saw God. It was there that John the

Baptist preached the coming of the Messiah. Indeed, it was in the desert

that Jesus Himself began His ministry; it was in the wilderness that He

was first tempted by the demons (Matt. 4.1-10); and it was in the craggy

areas of the Judaean mountains that He periodically withdrew to be alone and to

pray (Matt. 14.23). In fact, the early monks believed that a reference

in the Letter to the Galatians may also imply a brief sojourn by Paul in

the desert of Arabia immediately following his conversion.

When God, who had set me apart before I was born and called me through

His grace, was pleased to reveal His Son to me, so that I might proclaim

Him among the Gentiles, I did not confer with any human being, nor did I

go up to Jerusalem to those who were already apostles before me, but I

went away at once into Arabia, and afterward I returned to Damascus.

(Gal. 1.15-17)

So the desert, while accursed, was never seen as an empty region. It was

a place that was full of action. It was not an area of scenic views, in

the modern sense of a tourist attraction. It was a space that provided

an opportunity, and even a calling, for divine vision. In the desert,

you were invited to shake off all forms of idolatry, all kinds of

earthly limitations, in order to behold—or, rather, to be held before—an

image of the heavenly God. There, you were confronted with another

reality, with the presence of a boundless God, whose grace was without

any limits at all. You could never avoid that perspective of revelation.

After all, you cannot hide in the desert; there is no room for lying or

deceit there. Your very self is reflected in the dry desert, and you are

obliged to face up to this self. Anything else would constitute a

dangerous illusion, not a divine icon. Abba Alonios states this quite

simply:

Abba Alonios said: "If one does not say in one's heart, that in the

world there is only myself and God, then one will simply not gain

peace."2

The desert is an attraction beyond oneself; it is an invitation to

transfiguration. It was neither a better way, nor an easier way. The

desert elders were not out to prove a point; they were there to prove

themselves. Antony advises complete renunciation in this effort to hold

God before one's eyes at all times:

Abba Antony also said: "Always have the fear of God before your eyes.

Remember Him who gives death and life. Hate the world and all that is in

it. Hate all peace that comes from the flesh. Renounce this life, so

that you may be alive to God. Remember what you have promised God, for

it will be required of you on the Day of Judgment. Suffer hunger; suffer

thirst; suffer nakedness; be watchful and sorrowful; weep and groan in

your heart; test yourselves, to see if you are worthy of God; despise

the flesh, so that you may preserve your souls."3

Nothing should be held back in this surrender. It is all or nothing. The

abandonment to God is absolute. As a result, the rewards are either

fruitful or else frightening.

A brother renounced the world and gave his goods to the poor. However,

he kept back just a little for his personal expenses and needs. He went

to see Abba Antony. When he told him of this, the old man said to him:

"If you want to be a monk, go into the village, buy some meat, cover

your naked body with this meat, and then come here like that." The

brother did so. And the dogs and birds tore at his flesh. When he came

back, the old man asked him whether he had followed his advice. The

brother simply showed Antony his wounded body. Saint Antony said: "Those

who renounce the world but choose to keep back even a little for

themselves are torn in this way by the demons."4

The desert is a place of spiritual revolution, not of personal retreat.

It is a place of inner protest, not outward peace. It is a place of deep

encounter, not of superficial escape. It is a place of repentance, not

recuperation. Living in the desert does not mean living without people;

it means living for God. Antony and the other desert dwellers never

forgot this. They never sought to cut off their connections to other

people instantly. They sought rather to refine these relationships

increasingly.

Of course, the desert was, on a deeper level, always more than simply a

place. It was a way. And it was not the desert that made the Desert

Fathers and Mothers, any more than it was the lion that made the

martyrs.5

The Sayings contain many stories that reveal the desert as a

spiritual way that was present everywhere, including the large and busy

cities.

It was revealed to Abba Antony in his desert that there was someone who

was his equal in the city. He was a doctor by profession. Whatever he

had beyond his needs, he would give to the poor; and every day he sang

hymns with the angels.6

It is the clear understanding of these elders that one does not have to

move to the geographical location of the wilderness in order to find

God. Yet, if you do not have to go to the desert, you do have to go

through the desert. The Desert Fathers and Mothers always speak

from their experience of the desert, even if they do not actually

come out of that desert. The desert is a necessary stage on the

spiritual journey. To avoid it would be harmful. To dress it up or

conceal it may be tempting; but it also proves destructive in the

spiritual path.

Ironically, you do not have to find the desert in your life; it normally

catches up with you. Everyone does go through the desert, in one shape

or another. It may be in the form of some suffering, or emptiness, or

breakdown, or breakup, or divorce, or any kind of trauma that occurs in

our life. Dressing this desert up through our addictions or attachments

— to material goods, or money, or food, or drink, or success, or

obsessions, or anything else we may care to turn toward or may find

available to depend upon — will delay the utter loneliness and the inner

fearfulness of the desert experience. If we go through this experience

involuntarily, then it can be both overwhelming and crushing. If,

however, we accept to undergo this experience voluntarily, then it can

prove both constructive and liberating. The physical setting of the desert is a symbol, a powerful reminder of a spiritual space that is within us all. In the United States, the grand desert of Arizona can assist us in recalling that inner space where we yearn for God. In Australia, the frightening outback can also guide us in our search for that heavenly "dream-time." In Egypt, the sandy dunes of the desert resembled the unending search of these abbas and ammas for "abundant life" (John 10.10) and "a living spring of water" (John 4.14).

FOOTNOTES:

1. Elias 7.

2. Alonios 1.

3. Antony 33.

4. Antony 20.

5. Cf. The Wisdom of the Desert Fathers, ed.

Â

Ward (Oxford: SLG Press, 1975), p. vii (Foreword by Anthony Bloom).

6. Antony 24. See also K. Ware, "The Monk and the Married Christian," Eastern

Churches Review & (1974): 72-83.

|